Subtitling the D-Day 70th anniversary commemoration

Subtitling services

In the firing line today: BBC News 24.

The D-Day commemorations remembrance service did not show captioning of the words to the hymns or songs that were being played. The BBC news website is showing videos of the events and none of them are subtitled.

Where is our access? Where is the full access for the D-Day veterans themselves?

Did you know there are 10 million deaf and hard of hearing people in the UK?

Did you know that 3 in 4 people over 70 have some degree of hearing loss and can’t hear the TV, and need subtitles? We live in a fragmented society where loneliness is common for the elderly, and often their only contact with the world is through the television.

I have to tell you the subtitles for the D-Day service have been the most disappointing I have ever seen. Do you think we would know the words for all the hymns and songs off by heart? Just stating the name of the song they are singing isn’t the way to do it, we need the subtitles.

Most of the veterans are now in their 90’s – and a fair number will be hard of hearing now – so it’s even more important to make sure it’s fully subtitles – I am not a happy bunny with your subtitlers today – they can’t even get the names of the beaches right, they have messed up on several things…. I’ve seen several different ways of the phonetics of “Mulberry beach” and “Ohama beach” – surely if they were doing voice recognition, then they should have those in their dictionaries?

The subtitles had a long time lag – any delays between sound and captions makes comprehension more difficult for the reader.

That is they same story with subtitles all the time, a misspelling comes up and I’m struggling to work out the correct one, meantime the misspelling is corrected and I’m then racing ahead to catch up , only before I do the topic has moved on and I don’t know what they were talking about.

This infuriates me beyond belief! They try to correct the whole word about five times, especially when it’s actually quite close to the original, so you know what it is, then type the ENTIRE last phrase out all over again, creating a cumulative delay that’s difficult to claw back. When the word isn’t at all close to the original, leaving you to think “Eh what?”, the subtitles trip along merrily with nary a backward glance.

Watch this video clip of the D-Day remembrance service and imagine you’ve never heard the words to Auld Lang Syne and you see this – does it make you feel emotional without the sound, and without the words? Do you “get it” when there are lots of pictures and the words of “We’ll meet again” show up? – just one example of what it actually looks, feels and sounds like to someone reliant on subtitles. The spelling of the word “Syne” is wrong and the subtitles are right in the middle of the screen – they should be at the bottom.

The subtitles on the D Day 70th Anniversary cannot even get the names of the beaches right – “sought” for “Sword”.

At a London conference this week there was a lot of discussion about the importance of captioning for inclusion and accessibility, particularly for the elderly. We learned that accessibility is built into the production cost and amounts to less than 1% of the budget – so why is it almost an afterthought? We all deserve equal access.

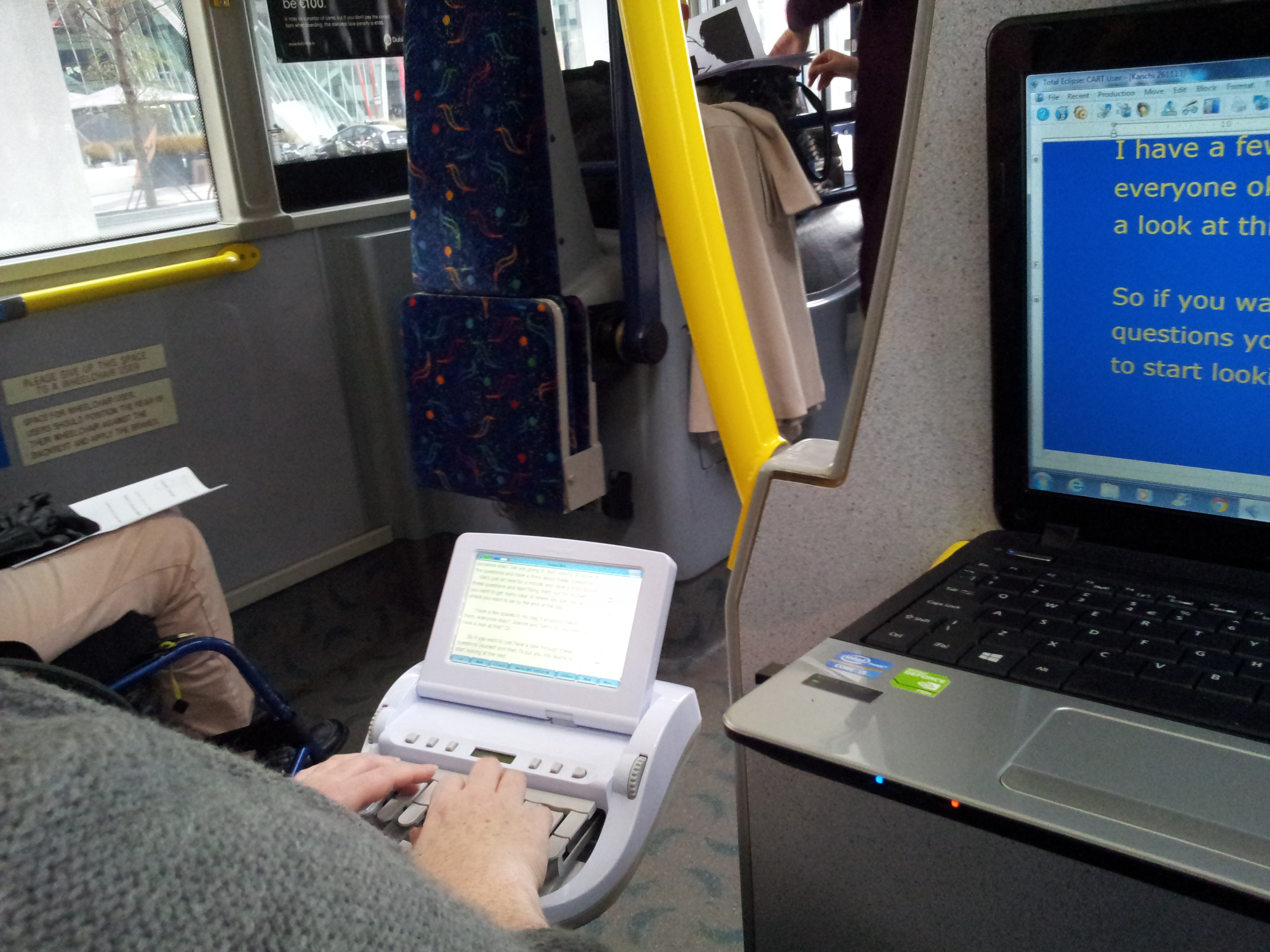

Funny how the other TV channels manage a far better service than the Beeb that we have to pay a licence fee for and they still can’t get their act together. They should bring back the Palantypists for live broadcasts. At least the accuracy from them is in excess of 98%!

We watched the D-Day highlights and the subtitles were much better than they had been during the live remembrance service, but they were several seconds behind. They had time to get it right – but did they make time to consider accessibility for deaf and hard of hearing viewers? It’s not hard to have a few seconds delay in the live transmission, to enable captioners to edit the text before streaming it. It’s not hard to have a bank of subtitles for hymns and songs, and trot these out as needed instead of shooting new footage or reinventing the wheel by respoking — respeeking – respooking – reinventing the wheel by respeaking (oh heck the subject’s now moved on and the captions are now 10 seconds behind).

The live subtitles were talking about the 17th anniversary!

The quality of captions is so important. The BBC has spent so much on respeaking technology and want this technology to work. The BBC has never, to our knowledge, asked deaf viewers what they think about the subtitling service.

The BBC’s history of subtitling

BBC Broadcast was created by the BBC in 2002, by placing a range of BBC channel creation and channel management services under one roof. It was part of an agreement with the British Government to create a commercial division that could supplement the BBC’s income from the television licence, thus keeping the licence fee increases down in the future. The other entities within the commercial division were BBC Worldwide, BBC Resources, BBC Ventures and BBC Technology.

On 1 August 2005, BBC Broadcast, together with its subsidiaries, was sold for £166 million to Creative Broadcast Services Limited, a company set up specifically for the purchase and jointly owned by Australian-based Macquarie Capital Alliance Group and Macquarie Bank Limited. The company was renamed Red Bee Media on 27 October 2005. Red Bee Media sponsored the recent caption quality white paper. This paper states;

In recent years, the quality of closed captions for the Deaf and hearing impaired (or hard of hearing) has become of an area of increasing concern for both caption users and industry regulators. Much of this concern can be traced to large increases in the volume of programs being captioned (driven by consumer demand and quotas imposed on broadcasters by regulators), and in particular an increase in live captioning. This is generally performed by stenocaptioners or, increasingly, captioners using speech recognition software (known as ‘respeakers’). For viewers, captions produced by stenocaptioning or respeaking have certain inherent drawbacks. There is an inevitable time lag between the audio and the captions appearing on screen, they are typically presented as ‘scrolling’ captions which appear one word at a time, they may be too fast to be easily read, and they are prone to errors. In some cases, the errors may be so bad that the captions are essentially useless. While viewers may dislike live captions, the fact remains that there are many programs, both genuinely live programs, and programs delivered very close to broadcast time, which can realistically only be captioned live.

In 2011, a group of deaf viewers tweeted and commented on Red Bee Media’s Facebook page about the poor quality of subtitles. Red Bee Media changed their Facebook page settings so none of them could comment or complain publicly. Today, the Facebook page has been removed – we have been robbed of a voice.

BBC News 24’s Facebook page has not been updated since Mandela’s death. This is not current news – this is OLD news. Yet again, poor access for those who need to read rather than listen. The videos on the BBC website do not have captions. There are more and more videos being uploaded and less text – access is actually decreasing.

How are deaf and hard of hearing people (including many D-Day veterans) supposed to be fully included?

When are the BBC and Red Bee Media going to ask us – deaf people, their customers – what we think of their subtitles? They should make subtitles an integral part of the programming – they should integrate rather than marginalise us. In April 2014, Ofcom published its first report on the quality of live TV subtitles provided by broadcasters in the UK.

Your website videos of the D-Day events have no subtitles either – if you can do it for iPlayer – what’s the problem? There are several videos and audiobooks on your website – yet none of them are accessible to deaf people, so why am I even bothering to pay a licence fee for a worse service?

How to complain about TV subtitling

Deaf viewers are not happy about the way the D-Day commemoration has been subtitled. There were no subtitles for the hymns – someone at the BBC expected us to know the words. The subtitles didn’t match the pictures. There were BBC credits at the end – let’s shout for equal access.

How to complain about subtitles

Nothing about us without us! Join the Caption Everything campaign. Add the logo to your website, Facebook profile, tweet it and let everyone know how important good quality captioning, and full access to it, is for everyone. Here’s a link to the campaign flyer: Caption Everything Together (PDF)

www.captioneverything.org

@Caption_All

#nothingaboutuswithoutus

Caption quality white paper 2014

Ofcom report on quality of live TV subtitles in UK