Blog

Say goodbye to single-sided deafness with Naída Link CROS

/7 Comments/in Diversity and inclusion /by Tina Lannin#ICAN : Hayleigh, hearing aid charms

/1 Comment/in Diversity and inclusion /by Tina LanninHi! I’m Hayleigh and I am 15 years old and the designer and creator of Hayleigh’s Cherished Charms. When I was 18 months old, I was diagnosed as severe to profoundly hard of hearing. When my parents heard the news, they made a decision that impacted my life forever. They hid my hearing aids.

At age 4, I attended a school for hard of hearing children. I noticed that a lot of kids tried to hide their hearing aids behind their hair. I wanted to make my hearing aids shine and be fancy. I wanted to be proud of my hearing aids!

I started drawing pictures along with my sisters showing how I could make my hearing aids shine. My mom helped me make our designs into jewelry and tube twists for my hearing aids. They were so fancy. Other kids and adults started wanting them too! And so with the help of my mom and dad, I started my own little business…Hayleigh’s Cherished Charms.

I have my own work area at my house where my sisters and I make all of our products for hearing aids and cochlear implants. All of our charms can be made into pierced and clip-on earrings too so that siblings, parents, and friends can match and join in the fun.

I have applied for several provisional patents on my creations and a full patent!

In October 2010, I was awarded first place in the student category for Oticon’s National Contest, Focus on People. They recognized my business because I am determined to help others feel confident and comfortable with their hearing aids!

I donate 10% of every sale to hearing research and schools that dedicate their time and resources to help the hard of hearing. It is my goal to help children and adults with hearing loss feel good about their hearing equipment while supporting the schools and research that help us!

Peer Lauritsen, the president of Oticon had this to say about me and my business….

Individuals like Hayleigh Scott are inspiring role models for people living with hearing loss. Through her achievements and contributions, she has shown us that hearing loss does not limit a person’s ability to make a difference in their families, their communities and even, the world. By recognizing outstanding individuals such as Hayleigh, we aim to motivate people to speak with hearing care professionals about hearing loss and the hearing solutions that can empower them to participate actively in all that life has to offer. – Peer Lauritsen, President of Oticon, Inc.

Since winning the Oticon award and opening my business, I have been interviewed for books, magazines, and been asked to speak at conferences and conventions. It amazes me how a little idea to help people feel better about themselves has blossomed into a full scale business.

My goals are to continually make quality products at affordable prices for anyone who wants them, to continue to have very personalized service, to actively support schools and research for the hard of hearing and deaf, and to inspire the young and old to celebrate who they are! Audiologist, Dr.Michele Labrie had this to say about my business ;

Hayleigh is one of the most inspiring and creative patients I have seen. She has embraced her hearing loss and hearing instruments in the most positive way to make herself even more beautiful than she already is. Her Cherished Charms have helped people of all ages feel more beautiful and more confident about wearing hearing devices.

Hayleighs Cherished Charms cherishedcharms@gmail.com

Lipspeaker v lipreader: A literary adventure

/0 Comments/in Diversity and inclusion /by Tina LanninGuest author: Deaflinguist

A fortnight ago I went to a conference in my academic field and definitely needed communication support for an intensive day of quite high-powered lecturing which was a challenge for my lipspeaker on several counts, not least that few of the speakers gave her any material to prepare, some had English as a second language, and others just spoke terrifically rapidly and had to be forcibly slowed down.

My lipspeaker was working solo since the other booked lipspeaker was ill, and she admitted to feeling as if she was struggling in the circumstances: however, she betrayed no sign of it and carried on as a true professional. We talked it over and came to the conclusion that because I was familiar with the field I could fill in the gaps from my own knowledge and supplement it with what I could hear. I think it helped as well being someone who was used to receiving communication support, and thus having an understanding of how it works and reasonable expectations.

The following week I went to a former colleague’s book launch in a church in Bristol as a social occasion, just with the Bear, who also knows him. Our friend gave a speech for 20 minutes which I followed in its entirety. OK, I knew the speaker, and had some idea of the subject, since we have a common background. Yet even with those advantages, I wouldn’t have been able to follow in the past by lipreading alone.

Thus emboldened, I dragged the Bear along to a local library a few days later, when I found out that an author of well-received historical fiction, based on his own researches which have overlapped with my own, was speaking. I’d never met him before so this was ratcheting it up a notch. Off we trotted and everything was in my favour – we were the first to arrive so had our choice of seats; small venue; nice bright lights which were not dimmed for the talk; a cleverly illustrated PowerPoint presentation; a clear speaker who was used to public speaking and thus spoke without hesitation, digressions, or backtracking on himself; and a manageable 45 minutes.

Again, perhaps, some prior knowledge helped me on my way, but I understood everything he said, apart from one or two occasions when he did put his hand to his mouth as he mused on something. However, I quickly picked up the thread again. Where I had some difficulty was in understanding the questions at the end, but the Bear repeated them for me and I was able to follow the answers. The issues, of course, lay in not seeing the speakers behind me (as I was sitting at the front), in the rather more random order of the questions, and in the demographic, of older people, the register of whose voices can sometimes have less clarity.

That week concluded with me giving a lecture to an audience of mostly older people. I knew that this would be a largish audience and that a certain number would, themselves, have age-related loss and be hearing-aid wearers, but would not request communication support, necessarily. We had a small venue with good acoustics which I requested specifically, no competing or intrusive noise, good lighting, and so on – all the things which worked for me the other way round as an audience member.

One of the things that I do as a speaker is to make the audience laugh a little bit every now and then – it’s not necessarily for entertainment value, to put them at their ease, or give them something memorable that will stick in their mind from the talk, although those are good things to do, but simply because it is a subtle way of checking that they’ve understood. If they all laugh together – they’ve got you.

For this audience, I requested a sign language interpreter as it is the unwritten law of presentations that the person who asks the most avid questions will be the mumbler with the beard at the back, and I won’t have a hope of understanding them. It’s less critical when I’m part of the audience myself. As a professional, though, it is crucial to comprehend questions correctly in order to answer them, but it is also important to put the audience at their ease, particularly with that demographic who may feel less confident about repeating their question if it isn’t understood first time. It went seamlessly and I was pleased that I had pitched the situation absolutely correctly and not gone swimming solo out of my depth.

The moral of the story is: don’t be afraid to stretch your boundaries with a cochlear implant and try new things, and the second moral is that it is always worth reviewing your communication needs, not only pre- and post-cochlear implant, but also for specific situations.

Cochlear implants for Irish children

/0 Comments/in Diversity and inclusion /by Tina LanninWe’ve had some fantastic news from Ireland. A campaign was run over the last year to have two cochlear implants as standard treatment for deaf children rather than just one. Most countries offer two cochlear implants to children, but this was not the practice in Ireland.

After a lot of hard campaigning and a petition to the Minister for Health, the HSE has now agreed to roll out a €3.2million bilateral cochlear implant programme with the Beaumont Hospital, Dublin.

One hundred cochlear implants were allocated in the HSE plan for 2014. The HSE hopes to offer more money annually for cochlear implants under each yearly budget/plan. Well done Minister Reilly for managing this achievement in a very tough health budget year and well done to the parents who fought tirelessly for their children to have the gift of bilateral cochlear implants.

From personal experience of receiving sequential cochlear implants, I can confirm that having bilateral hearing is totally different from hearing in just one ear, it is much easier to understand speech and other benefits include directional hearing.

There have been some who have not agreed with the petition’s aims and do not think deaf children should be offered cochlear implants. In response to those in disagreement, Denise Martin speaks of her dreams for her deaf daughter now being realised.

I didnt have this operation lightly for my daughter. To say her job opportunities would not be limited is ridiculous. My Daughter is 3 years old very bright her only set back is her hearing. She was tested at 110db her brain did not respond to sound. If a jumbo jet landed beside her head she would not hear it high powered hearing aids gave her no access to sound. My little girl would never have learned to talk when she had her operation she had no words. How can you tell me a girl who cannot hear cannot speak is not limited in her job opportunities. How can she grow up go to college be a Doctor Or President of Ireland. How can she work in a call center answering the phone, work as a receptionist, work in a shop as a cashier and listen to customers and answer their questions. How absolutely dare you tell me not to fear the worse for my Precious little princess you have no idea what it is like the frustration on her little face for 2 years before she was implanted with this miracle of a cochlear implant. I have opened up a world of possibilities to my little girl that never would have been possible. How many profoundly deaf non hearing non speaking Doctors do you know? How many world leaders could not hear or speak ? How many Barristers Cannot Talk? How Many Ceo’s of companies cannot hear or speak?????? I have big Dreams like every parent for my little girl. How dare you tell me i should be happy to hold her back and not let her reach for the stars. Next time your listening to Music the Tv or even the birds singing think of my little 3 year old daughter and think i have chosen to give her the gift of sound to enhance the quality of her life something you so clearly take for granted. Just imagine you could not hear those sounds just try think for one minute never hearing music again. I want her to live life to the full not simple muddle along as you would have her do. Watch this space as in 30 years from now she could be a Doctor who can talk to her patients or CEO of a company who knows i want her to reach for the stars and have all she wants as a hearing speaking successful woman that nothing can hold back. Unless you have a profoundly Deaf Child with no speech you cannot judge my decision or other parents. I respect all parents choices to make the right decision for their family as we did for ours. Every day i am reminded of just how correct we were in our decision.

Ginny Kanka: Me and my cochlear implants

/0 Comments/in Diversity and inclusion /by Tina LanninThe vocal sounds I’ve heard have always come via hearing aids ever since the first one in 1949. The early hearing aids were amplifiers. Hearing people have explained that the vocal sound becomes more distorted the louder it gets. According to my hearing brain, the “distorted speech” sounds clear and normal to me.

From the moment I had my first hearing aid (consisting of two Ever Ready portable A and B batteries in a bag and a huge black receiver with a silver spring-clip – was this casing made of Bakelite?), I loved it. From that point on, to be without a hearing aid was total anathema to me.

By the time I was a teenager, the behind the ear (BTE) hearing aids were around but I was too deaf to have them. Over the next twenty years, the more powerful the BTE became the more deaf I became! Wearing the body worn hearing aid was the only option.

The usual home for my body worn hearing aid was in my bra. Pregnant in 1983, I was determined to have the BTE hearing aids as I wanted to be physically free to breast feed my babe-to-come. Shifting boobs was problem enough let alone the thought of shifting my body hearing aid around for breast feeding. Glorious it was to strut around at home in my bulging birthday suit with new NHS BTE hearing aids on.

By 1989, I was desperate for more powerful hearing aids and also wanting to know why I was losing so much of what was left of my residual hearing. An appointment was made to see Graham Fraser in 1990. Quite quickly, he suggested I look into cochlear implants (CI). That was shocking news. I had heard about CIs and they were being implanted in people with APHL (acquired profound hearing loss) who on the whole were the more successful recipients than those with congenital deafness.

Considering that the success rate for prelingually deaf people was poor, I refused to think about CIs; besides, I had a young son and I was not ready.

All my life, I have had tinnitus. As child, teenager and in my twenties, I didn’t know it was called tinnitus. Just noise of different kinds came into my ears often; I was not at all annoyed by them. I kind of saw them as friends who came and went. When they came, I simply said hi to them and put them out of mind. In other words, I could manage them.

Around 1993, the tinnitus changed and became sharper, shrill and bad tempered. Over time, the breaks between them became shorter and the noise longer lasting as if a Duracell battery would never run out. It sounded as if a million knives were scraping one another and a trillion of birds screeching; impossible to ignore them. Fed up with the harassment, I went to a tinnitus clinic – was it in 1995? I can’t remember. The consultant there took one look at me and told me to go to the cochlear implant clinic. Methinks, what an odd treatment.

As I had nothing to lose, I agreed to go for the cochlear implant. On switch-on day in April 1997, oh boy, it was wonderful! I heard no voice sounding like Donald Duck as usually experienced by new implantees. Hearing-wise, I was back to my time as a teenager with powerful body worn hearing aid.

In the meantime, I was in a state of surprise as the exhausting ‘evil’ tinnitus had stopped. It took me a while to get used to the sheer silence. Much later, I understood what had happened or rather a theory which made complete sense to me. If one loses a leg, the brain signals to the amputee that there’s pain in the non-existent leg, known as the phantom feeling. In my case, the more I lost what was left of my hearing, the stronger the ‘phantom’ noise became. Once my auditory brain got the noise back via my cochlear implant, it no longer had to make imaginary noise to feed itself. For that reason, a heartfelt vive la CI!

For several years, the CI body-worn processor, with a red light flashing for every sound heard, was tucked into my bra. In a way, I was sorry to say good bye to my red light district when I received an upgrade – a Cochlear™ Esprit 3G BTE processor, compatible to my internal Nucleus® 22 channel.

Wonderful opportunity came a few years later with another upgrade, a Freedom®. Eighteen months later, my auditory world changed when I had a convolutedly active face. I noted the facial spasm was in tune with whatever noise was going on around me, behaving just like how the body worn CI processor’s red light flashed.

One of the internal electrodes had turned rogue and was ‘hitting’ on my facial nerve. This electrode was turned off and all was fine. It happened again the following week, and another electrode was turned off and all was fine. Fascinating experience, I thought. Soon, it was not funny when it repeated again and again. My listening ability went downhill. I was just plain unlucky after fifteen good years with the cochlear implant.

Marisa and Jane, the two CI audiologists, worked really hard to get the best with various modes of stimulation and other adjustments. The comfort level (loudest sound heard and is tolerable) could not be enacted on the rogue electrodes. A new level – what shall we call it? – I call it “eyenotic” level*. The speech sound at eyenotic level is quieter than the comfort level but at least my face is calm.

*(no twinge or tic in my (right) eye, phonetically ‘eye-no-tic’)

By September 2012 after seven months with gorgeous Marisa and Jane trying every which way to improve my listening ability without triggering facial spasm, they finally suggested I have a think about a new internal implant.

Admittedly, I was put out of kilter when reimplantation was suggested – then relieved. As long as I remember how much easier and less tiring it was when I used to hear better.

My eyesight has never been brilliant since birth; I see well but on a smaller scale. I don’t see wrinkles unless I come close to people’s faces; in poor light, a magnifying glass helps. Since the onset with the problematic electrodes, when attending talks or stage performances which are supported by speech-to-text on screen or caption boxes, I noticed that seeing the text is worse because I can’t hear as well as I used to.

Beginning of October 2012, I contacted the CI team, asking them to kick start the funding scenario. Indeed, it is a gamble.

Why should it be a gamble? Would the reimplantation really solve the problem? CI team did say that the new internal slim line model would not splay impulses on my facial nerve. I’m not convinced.

When I had the implant in 1997, I had nothing to lose as I had the back up from my unimplanted side (left ear). At the time, it was the policy not to wear hearing aid as a crutch with the CI. The listening ability on the left had diminished, proven to me years later when the ‘policy’ changed tracks; I tried hearing aids and it was a no go area.

The meeting with the CI team was surreal. After discussion, Mr Lavy the surgeon confronted me with the definitive question. I have two choices, to go for it or not. I said that I have a lot to lose if I go for reimplantation and it goes wrong. The air in the room turned cool and the silence deafening.

Then a light bulb lit up on the surgeon’s face as he exclaimed how about an implant on the other ear. Oh my, everybody including me in the room – our minds were thinking – what a turn around. Perfect solution and I was so happy with the idea.

Funding came through and I had the operation and a month later, in June 2013, the switch-on (using the Nucleus® 5 system). I expected no miracles from the switch-on as the left ear brain hasn’t heard a thing for eon. Would it be three weeks, three months or three years before left side neurons cotton on to what they are supposed to do with the noise?

During the switching on process for the threshold level, at first I couldn’t hear a thing then I felt I had an auditory illusion which became real. As for setting up the comfort range, my emotion peaked, quivered and shocked as the left ear heard the sounds after a long gap of time.

Finally the switch-on came. Everything squeaked and beeped. I spoke and my voice beeped. This is ridiculous. Will, my son, said that my voice was normal. Beep, beep, beep. Where was the Donald Duck noise? Beep, beep, beep; perhaps just as well as I have no idea what Donald Duck sounds like!

Luckily for me as each time I heard a new noise at a certain frequency and decibel, the reawakened left auditory brain acknowledged the sound with a beep then never again.

The next three months was a time of sandwiches filled with ultra high delight at picking up new sounds (some no longer heard by the old side) and so low with frustration on managing the volume and sensitivity. Couple of the ‘electrodes’ on the new (aka sequential) CI did trigger twitching on the other side of my face and had to be set at eyenotic level and not, alas, at comfort level.

Though I concentrated on listening with just the sequential CI on and the old one off most of the time, I did practice with both processors on and the marriage between the two was stormy; the old side still wore the trousers.

Early August, CI audiologist explained that those who have a sequential (aka 2nd implant) all without doubt use the 1st CI ear as the main and preferred listening device. At that point, tears burst out. Damn it! It was my intention to stick out on the sequential processor and improve its listening ability, and obviously that had subconsciously put me under stress. Good riddance to my commitment scheme and I can now relax, using both and get their marriage to work.

Meanwhile I had been told that as I had my operation in May, I was eligible for the Cochlear™ Nucleus® 6 processor upgrade. Whoa! The opportunity came at end of August. Very simple swap over on the day and I also asked for the old side to be remapped, now more sure the whereabouts the twiddling should took place to make the processors’ marriage more heavenly.

The shaky honeymoon is over, and the binaural relationship is excellent. Neither side is showing who the aural boss is. The sequential ear needs more practice in recognising and identifying the incoming vocal sound (which is different from being “heard” and seeing it from lipreading).

When I think of Bakelite 78 rpm records and today’s music on iPods, I think of my 1949 hearing aid and today’s CIs. Stereophonic hearing delight indeed!

Understanding cochlear implants and hearing aids

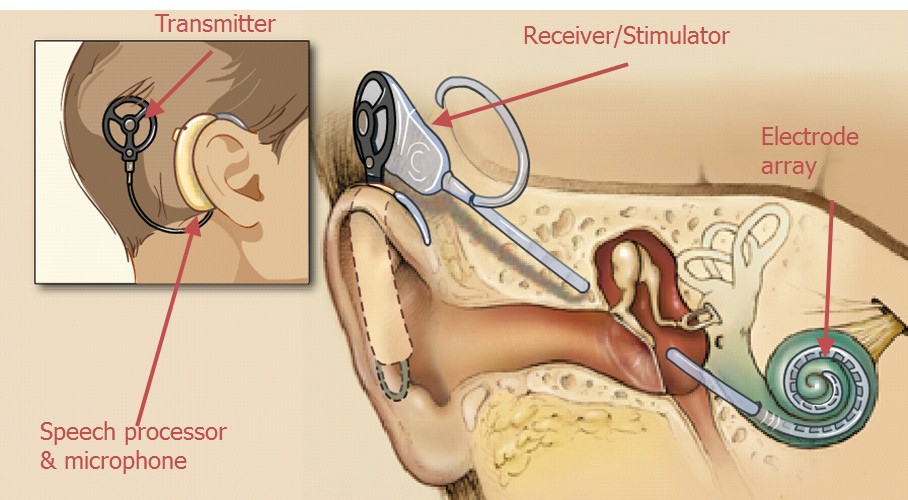

/0 Comments/in Diversity and inclusion /by Tina LanninWhen you’re trying to find a solution to your hearing loss problems any device or procedure can seem like a glimmer of hope, especially once you’re introduced to the concept of cochlear implants. While both hearing aids and cochlear implants are designed to provide listening assistance to the hearing impaired they’re used for different purposes and their operational attributes are anything but the same Here are the main differences between cochlear implants and hearing aids:

Primary Differences in Functionality

First of all, hearing aids are devices that amplify sound waves in certain frequencies and then project those sounds towards the inner ear where they can be processed by the auditory nerve. This is the main goal of a hearing aid – to capture, analyse, and amplify sound waves in order to correct specific frequency-based deficiencies in hearing.

A cochlear implant on the other hand is designed to capture the sound with an externally located receiver and then transfer the signal to an in internal stimulator that is surgically implanted into the mastoid bone behind the ear. The stimulator then translates the sound signal into an electrical impulse that is sent along the auditory nerve directly to the brain to be interpreted as sound. For this reason you can’t make on-the-go adjustments to the sound preferences in your cochlear implant and the features are much more limited.

Primary Differences in Cost and Maintenance

A cochlear implant surgery can be expensive if you don’t have any financing or insurance to assist you with the cost. When you consider the fact that you’ll be stuck with that model of implant for quite a while (as another surgery will be the only way to upgrade) you’ll realize that cochlear implants are more expensive in the long run.

You can buy one pair of hearing aids and then trade them in for an upgrade with your supplier in a relatively flexible manner, upgrading as you see fit when new technology becomes available. Hearing aids are also easy to remove and thoroughly clean; most come with a manual on how to perform maintenance and even accessories like ear wax removal kits.

Furthermore, performing maintenance on your cochlear implant is not something that can be done at home, as can be done with a pair of conventional hearing aids. That is of course unless you’re willing to perform surgery on yourself and attempt re-implanting the device in your skull (neither a feasible nor safe endeavour to attempt).

Conclusion – Which Should You Use?

Realistically cochlear implants and hearing aids should not even be compared because individuals who are truly in need of a cochlear implant would likely not benefit greatly from hearing aids and vice versa. If you have slight hearing loss then cochlear implants are probably not an option you want to consider, as the surgery and costs involved are not warranted unless your hearing loss is severe. Therefore, individuals with minor to moderate hearing loss should opt for a pair of hearing aids that they can easily replace or adjust if need be. Individuals with severe hearing loss may want to consult with their audiologist about the possibility of opting for a cochlear implant. In summary, a cochlear implant is the best option only when it is the only practical option left.

Author Bio: Paul Harrison is a knowledgeable and experienced blogger specializing in covering topics that help people make decision in their everyday lives. He’s currently venturing with YourHearing.co.uk, a leading retailer of assisted listening devices in the United Kingdom.

Hearing impairment? Try cochlear implants

/0 Comments/in Diversity and inclusion /by Tina LanninA hearing impairment can be A Good Thing

What is a cochlear implant and how does it work?

There are estimated to be over a quarter of a million people worldwide who have been fitted with a Cochlear implant and this number is growing all the time. It isn’t a miracle cure for deafness or hearing loss but the benefits that many people experience have greatly increased their quality of life.

So what is a cochlear implant?

A cochlear implant is a sophisticated electronic device that consists of two parts. There is the external part which contains the microphone and sound processor and an internal part that must be surgically implanted into the mastoid bone which is just behind the ear. Electrodes are inserted into the cochlea which receive the signals from the external processor.

What’s it for?

The name Cochlea comes from the Latin for ‘Snail Shell’, referring to its spiral structure. It is the auditory part of the inner ear and is divided into three separate chambers that process the different sound frequencies. Within these chambers is a fluid called Perilymph and tiny hairs called Cilia. When vibrations enter the cochlea it causes the fluid and hairs to move. When this happens, the brain will then interpret this movement as sound. For some people, this system doesn’t work often causing severe hearing impairment and even profound deafness.

How does it work?

This implant works by bypassing the parts of the ear that are not functioning correctly and directly stimulates the auditory nerve. The external microphone and processor picks up the sound and converts it to an electrical signal which is then sent to the implant under the skin. This is then transmitted down to the electrodes in the cochlea. Tiny electrical impulses then mimic the natural vibrations in the inner ear and send these signals to the brain as sound.

Who are these implants suitable for?

Cochlear implants are suitable for people who suffer with a severe or profound sensorineural hearing impairment and do not benefit from wearing a hearing aid. An in depth history of the person’s hearing loss will be taken as well as tests to determine the degree of loss and any possible medical causes. Other factors are also taken into account such as general health, state of mind and realistic expectations about what the results of the procedure are likely to be. As this procedure requires significant adjustment, the amount of family support available will also be looked at. These implants are often used for deaf children as they can help them learn language and speech and make school easier for them. For adults it can be a way of gaining more independence and confidence in their everyday lives.

What are the benefits?

Although the cochlear implant is not a cure for deafness or a hearing impairment, it can make a significant improvement for people who have had no success with other hearing solutions like hearing aids. Unlike a hearing aid, the implant does not make the sounds louder, it stimulates the auditory nerve directly delivering a better sense of sound. This means that someone with this implant can hear speech more clearly and will have a better awareness of the sounds in the environment around them.

Isn’t that major surgery though?

It is classed as major surgery but as it does not include any vital organs, it is not considered a high risk procedure, but like any surgery, there is always a certain degree of risk involved. The operation will last anywhere from 3 to 5 hours and a small portion of the hair must be shaved just behind the ear. The surgeon then attaches the implant to the mastoid bone and creates a pathway directly to the middle ear so the electrodes can be inserted into the Cochlea. You would normally spend 1 or 2 nights in hospital after the surgery before going home. Most over the counter pain relief such as paracetamol or ibuprofen should be adequate to deal with any discomfort and the stitches will dissolve after a few weeks. You will be advised not to wash your hair for at least a couple of weeks following the surgery. After 4 to 6 weeks you are required to make a return visit so the device can be activated and programmed. You will also be required to return for a number of tuning sessions to ensure you are getting the best sound quality possible from your implant.

Are there any side effects or restrictions after the surgery?

Any side effects are usually temporary but can include dizziness, numbness around the area of the operation, altered taste or tinnitus.

In regards to lifestyle changes, you can mostly carry on as normal but will be advised to avoid any sports that carry a risk of head injury or deep underwater activities such as scuba diving due to the pressure.

Due to the intensive screening process that each potential patient has to go through, this procedure has an extremely high success rate, exhibiting excellent results in a high percentage of users. Although the implant can give a better quality of hearing, things will never sound the same as they would with a normal functioning ear. Many people will find that they need to see a specialist to help adjust to the changes and get used to the difference in sound. Overall though, these Cochlear implants are providing a new lease of life for many who have previously felt isolated from the rest of the hearing world.

Author bio:

Paul Harrison is the Director of hearing aid specialists, Your Hearing. He has provided many resourceful articles over the last few months, he has covered topics including ways to naturally improve a hearing impairment, the different types of hearing aids and the benefits of using a hearing aid. Your Hearing helps people who have lost their hearing improve it and enhance their lifestyles.

The glory of artificial hearing

/0 Comments/in Diversity and inclusion /by Tina LanninMolly Brown was left profoundly deaf after her auditory nerves were removed during treatment for a genetic illness. In 2003 she became one of the first people to be given a radical new type of implant that attempts to recreate hearing by stimulating the brainstem directly. Of the five who received the implant, she has had the most success. She still finds the telephone difficult, so when she told Duncan Graham-Rowe about her strange new world in 2004, they used instant messaging.

When did you first notice problems with your hearing?

In 1982, when I was 22, I noticed I was having some difficulty talking on the phone. The sound seemed to be getting softer and more garbled.

What did you do?

I went to an ear doctor, who diagnosed “sinus difficulties”. But it was getting worse, so after another year I switched doctors. My new doctor straightaway suspected a brain tumour. He said, “You are too young to lose that much hearing.”

What was the diagnosis?

I had neurofibromatosis type II (NF2), although it wasn’t diagnosed for certain until last October. It is a disease in which chromosome 22 basically tells your body to develop non-malignant growths or tumours on the hearing nerves, spine and sometimes elsewhere in your body. It is present at conception. You know, I almost feel better knowing that I have had this from day one and that I was not doing something ”wrong”.

So you had the tumour removed?

Yes, and they had to remove the cochlea with all the auditory nerves as well, so I was left deaf in that ear. After that the hearing in my good ear fluctuated wildly. There was a small growth on that cochlea too. That growth had to be removed, which damaged that cochlea and left me completely deaf. When my newborn son was just three weeks old, I awoke to zero hearing. So I decided to have an implant in the damaged cochlea.

How long were you profoundly deaf before you had the cochlear implant?

About three years. My doctors felt I was not emotionally or mentally ready to receive a cochlear implant. I was absolutely devastated at my deafness. It is hard to put into words. I was so lonely, so terribly sad. There was no guarantee a cochlear implant would work, so my doctors and my family wanted me to “accept” my deafness so I could move on. And I did.

When you eventually had the cochlear implant put in, how well did it work?

It worked very well, especially at the beginning. I spoke on the phone frequently, and did extremely well where I could combine it with lip-reading. I loved it.

But it didn’t last. What happened?

Last summer, I began having awful facial pain on the right side. I thought it was a tooth. I give my dentist a lot of credit for figuring that it might be a brain tumour. The pain is known as trigeminal neuralgia – the worst pain known to medical practice. It felt like I was being electrically shocked.

What happened next?

My local doctor in Seattle had to do an MRI scan to get a better look at the tumour, and that meant removing the cochlear implant. You cannot have that much metal in your body with an MRI scan because it interferes with the imaging. My doctor promised me he would put it back if the tumour was not on the hearing nerve. Unfortunately it was, so that cochlea had to be removed too.

What did it feel like to know that you might be left profoundly deaf again?

Ah…I asked my children to tell me they loved me, because I might never have heard their voices again. I wore the cochlear implant right into the operating room where they did the MRI scan. My audiologist had tears in her eyes when she said she had to take it out. I wondered if hers would be the last voice I would hear in my life. I was devastated.

But after about six months, you did hear again…

Yes. They gave me a “penetrating electrode auditory brainstem implant”, which is a surgically implanted hearing device that attempts to replace the actual hearing nerve by electrically stimulating auditory nerves in the brainstem directly. It is still only in trials; there was no guarantee it would work. But for me, it has worked splendidly, especially when you consider I have zero nerves to my brain for hearing. I can control it myself via a signal processor that translates sounds into electrical stimulations. I can control the volume.

What was it like when they turned the device on? What did you hear?

It was one of those moments you never forget. Steve Otto, my audiologist at the House Ear Institute in Los Angeles, set me up with his computer to test if it worked. I tried not to watch their faces too much. I tried to concentrate on whether I could hear any sound. I waited. I knew he was turning it up. And then there it was. So soft. It was a series of beeps. I just said, “There.” I was perfectly calm, but inside I could have jumped in Steve’s lap and shouted, “Yahoo!”

After the test, whose voice did you hear first and what did they say?

It was Steve’s. He punched a button, and there was his voice…beautiful! He said, “Listen to my voice. How does it sound? Testing one, two, three, four, baseball, cowboy, hot dog.” I can remember. If I lived to be 1000 years old I would never forget it.

How does it feel to be able to hear again after being profoundly deaf?

About how you would think! I am thrilled, pleased and happy beyond words. You must remember that I was facing a life with absolutely no sound. To have this is beyond miraculous, and I am ever so thankful. I am sitting here typing and enjoying the click-clack of the keys.

How does it compare with when you had a cochlear implant?

I am always surprised at the similarities. It is not exactly the same. But I compare them very favourably, which I was not expecting. I was expecting to hear mostly beeps. I would say that for speech I may have done a bit better in the very beginning with the cochlear implant. But not near the end.

What can you hear?

It seems like I hear everything. I hear amazingly soft sounds, such as the bubbles in a glass of soda, or pepper hitting a dinner plate. My family also tells me that my speech is better. I can hear my own voice again. But it is speech comprehension that I am really after. The bubbles in a glass of pop are just icing on the cake.

Are you having to relearn how to understand speech?

Yes, I am. I frequently try to understand people without looking, but it is so much easier to combine with lip-reading. I am lazy. As for the phone…

That’s the acid test in artificial hearing. How well can you understand people on the phone?

I call it my love-hate relationship. I so want to do it. I hear it ring and think, “Just pick it up!” I talked to my daughter recently, and she said something which I felt had nothing to do with what I was asking. I get all confused, then it goes out the window – mostly because we start laughing too much – but I’ll never get it unless I try. I did call Steve in Los Angeles one morning, which was a big deal for me. I heard him laugh at something I said. These things are a real accomplishment for me.

Do you think your hearing has been enhanced in any way compared with your natural hearing before all this began?

Oh, I do. I know I hear things that others don’t. I hear metal detectors in buildings buzzing, and when I ask others if they hear it they always say no.

How different do things sound now compared with before your hearing problems?

My memory is very clear on sound. Things such as car horns or water running are very similar. Music is very different, but my daughter plays the piano for me to get a feel of each note and how they sound now. But when people speak it sounds like they are speaking in an extremely growly voice with their hand muffling their mouth. I can always tell a man’s voice from a woman’s without looking. I am learning the environmental sounds, to differentiate between, say, someone speaking to me and the food mixer running.

Do things sound artificial?

Oh, it’s very artificial. Very synthesised. But the longer I use it and get used to it, the more natural it sounds. The brain is pretty adaptable.

You recently went back to the House Ear Institute for a “retuning” to help improve your speech comprehension. Can you explain what they did?

The device has different types of electrodes. Some sit on the surface of the brainstem, others penetrate it and try to target a greater range of nerves and frequencies. When I go for reprogramming, Steve changes the way I hear. So I need to practise using it all over again. The penetrating electrode program may have been too loud previously, it was sounding as if I were standing under high-voltage power lines. Steve turned it down a bit. I am still asking people around me, “what was that sound?”

Do you think you will ever become so accustomed to your new hearing that you forget how things used to sound?

I will never forget. When I watch a singer on TV singing a song I know, I remember. It tugs at your heart. But my joy at hearing anything at all overrides that.

Given the dangers of tampering with the brainstem, weren’t you scared of the risks? Only one person had had the implant before you and there were no results at the time…

I had no fear, zero. It felt like my millionth brain surgery. I felt a lot better about trying it than if I had always been wondering if I should have. It was my impatient nature. I felt almost driven to try. I’m no hero here. That title belongs to the researchers and audiologists who slave over these inventions every day.

What were your expectations?

They said there were no guarantees that I would hear any sound at all. There are many repercussions from having a brain tumour removed. Besides the deafness, my face looks as if I have had a stroke. My eye would not close, so I had a metal spring implanted in it to open and shut it. In short, it is a difficult deal. I had zero expectations. Of course you hope, but I was trying to prepare myself for a lifetime of no sound.

What motivated you to volunteer?

My children. They have a 50 per cent chance of inheriting NF2 from me. I so wanted to show them that you should not be afraid to try things, that you don’t need to be fearful. Plus, I want as much research into NF2 as possible.

Do you know whether any of your children have NF2 or will develop it?

Thanks be to God, they look clear of it. They recently had MRI scans, which were clear. I would give my life for them, of course. I would give back this miraculous hearing if they would be free from NF2. But it looks very good for them. They are 25, 22 and 18. We have talked about the “what-ifs”. If any of them did develop NF2 I would counsel them and totally leave it up to them. The only test available thus far is the MRI. Again, I want more research so they will be able to check newborns and catch these tumours when they are small.

But with NF2 the tumours can reoccur...

Once the hearing nerve is removed, most people do not develop more tumours in the hearing section of the brain. I do have one teeny tumour on my spine. I am lucky, as many NF2 sufferers are really bothered by spinal tumours. In severe cases, they have to use wheelchairs.

Do you turn your device off at night?

I do take it off at night. And once I am out, I am gone! I do occasionally sleep with it. I can hear traffic from about half a mile

away and it drives me nuts. But I can turn it off. Sometimes I get all tense at sounds I am hearing, or when people are annoying me. But then I remember, ah, I can turn it off!

Source: New Scientist