Captioning and Access to Work

“Access to Work tell me to use X. I prefer Y.”

“Access to Work have told me to use a typist.”

“Why don’t you get a telephone with a flashing light? It’s cheaper.”

“My Access to Work adviser says I can only have up to £xx/hour for captioning.”

Sound familiar?

Requesting funding from Access to Work can be a minefield. What are you allowed to ask for? How can you get the type of captioning service you need? What are the differences in the captioning services available and how do they work? Can I use different providers? We look at answers to these questions and more in this article.

Access to Work will grant funding according to (1) the most economical service that (2) meets your minimum needs. However, the cheapest service is not necessarily the most appropriate one; it should also adequately meet your communication support needs.

Minimum needs

If you are in a professional level job and require equal access to work with your colleagues, then you will require verbatim captioning to put you on an equal footing with them. You will need verbatim steno captioning, also known as speech-to-text, which can keep up with fast speakers. This is different from respeaking, which is not verbatim and cannot keep up with fast speech.

If you’re a lipreader and require minutes of your meeting (as a lipreader can’t lipread and take notes at the same time), or you are a sign language user, or you simply do not require a word-for-word account of what is said, you can choose specialist electronic notetaking. An electronic notetaker is not verbatim. They can write a meaning-for-meaning account of what is said, rather than word-for-word.

How different captioning services work

- Verbatim captions

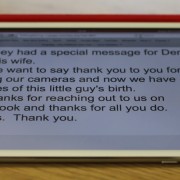

Verbatim captions are provided by a speech to text reporter (stenographer or palantypist) in the UK, or a CART provider (Communication Access Real-time Translation: stenographer) in the USA. This person uses a shorthand machine. They listen and process what is said in their brain, then write words on their machine. So the accuracy comes from their brain, not the machine, just as if you’re typing. It’s not relying on software to get it right. Therefore, this service is de facto much more accurate than voice recognition software. They are able to keep up with fast speakers and write every word.

The stenographer is able to correct any words after they appear on your screen, they can just go back and edit them. Any errors will be made from hitting the wrong keys or from not having a word in their dictionary – they can then finger spell a new word.

The latency is 1 or 2 seconds which means you would be able to take part in a meeting just like a hearing person, with a very small delay. This is important for your professional reputation at work; you need to be able to keep up with your hearing colleagues.

- Non-verbatim captions

Respeaking uses voice recognition software such as Dragon. It’s not very accurate. Much depends on how well the software recognises the respeaker’s voice and translates it into English. They have to speak at a slow steady pace for the software to understand what is being said. Respeaking does not work well when there is a fast speaker in your meeting, the software just can’t keep up.

An editor is needed to correct the errors, so a respeaker and an editor work in pairs. This slows down the latency i.e. The speed at which you receive the words, to 8 seconds. It’s still inaccurate as they are relying on the software to get it right, not their brains. This may mean omitting words and sentences in order to keep up. They also can’t go back and correct a word on screen if it comes out wrong, because the end result of the process, when the words appear on your screen, is the end of the process; they have already “edited” it. You are also paying for 2 people.

This blog post explains the differences between respeaking and stenography.

An electronic notetaker will listen and write what they hear on a Qwerty keyboard, which is used with software that has shortforms added to enable them to write the gist of what is said. The notetaker, like the speech to text reporter, is relying on their brain for accuracy, not their software.

Speech to text reporters and electronic notetakers offer the client protection under NRCPD. Respeakers do not – and they do not understand deaf voices. Communication support works both ways; it benefits hearing people at work too.

Access to Work

You are allowed to choose your preferred communication support provider, providing you choose one who is the least expensive and also meets your minimum needs. The government have imposed a yearly cap on communication support of £60,700 per year; this can be used for a mix of different support needs, and rolled over from month to month.

Access to Work are not allowed to dictate which service provider you should use or how much you can spend per hour; the choice is yours to make. If Access to Work try to make you choose a provider you don’t want to use because they say they do not meet your needs, they are putting barriers in your way, and you can take your case to PHSO. The PHSO team are very experienced in dealing with deaf Access to Work clients and they understand the differences between communication support services.

As 99% of deaf people do not use sign language, your minimum need is likely to be for verbatim English, because you need to have equal access to your hearing colleagues. You need to explain why you need a verbatim service to your Access to Work adviser.

If your preference is for a summative transcription, then you need to explain your choice to your adviser.

If you’d like further advice on how to obtain the appropriate support from Access to Work, contact Darren Townsend-Handscomb at Deaf ATW, or contact us for advice on captioning support.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!